Contemplative prayer

This weekend I shared the “Contemplative Prayer” video with some of my new chaplain friends who serve hospitals and prisons in Cuba. I was glad to share this video in particular because it has new Spanish closed captioning.

One chaplain asked a helpful question. In essence, what is the prayer of silence for? To listen to God, to prepare my response, to relax and avoid burnout?

I understand several reasons to practice contemplative prayer

1) Communication in prayer (talking to God and listening for a word from God) is good but communion with God is deeper.

2) In ministry the words we say are not as important as our presence and our loving attention, so it is with prayer also. Being present to God and noticing God’s presence for us is more profound than all the words we say.

3) Silence is God’s language, and it is the only space that can hold all of the terror and fear and grief and difficult things of life.

4) When we trust in God to hold all aspects of our lives, we are more calm and present to step into difficult places with people, and be companions with God in holding their difficulties.

5) Yes, it is restful to pray in this way, yet more importantly, it is an essential source of life and energy for our work of ministry.

There came a time in my travels through congregational ministry when I felt like simply ran out of words. All the words I used to pray, publicly and privately, felt empty and in vain. You can hear my story of what happened when I reached that point in this week’s episode of Three Minute Ministry Mentor.

Practicing contemplative prayer contributes to my healing and openness to change at pivotal times in my life. How has praying in silence supported you?

More on Contemplative Prayer | video | blog | podcast

Learning in Practice from my Past Self

4-8-2021

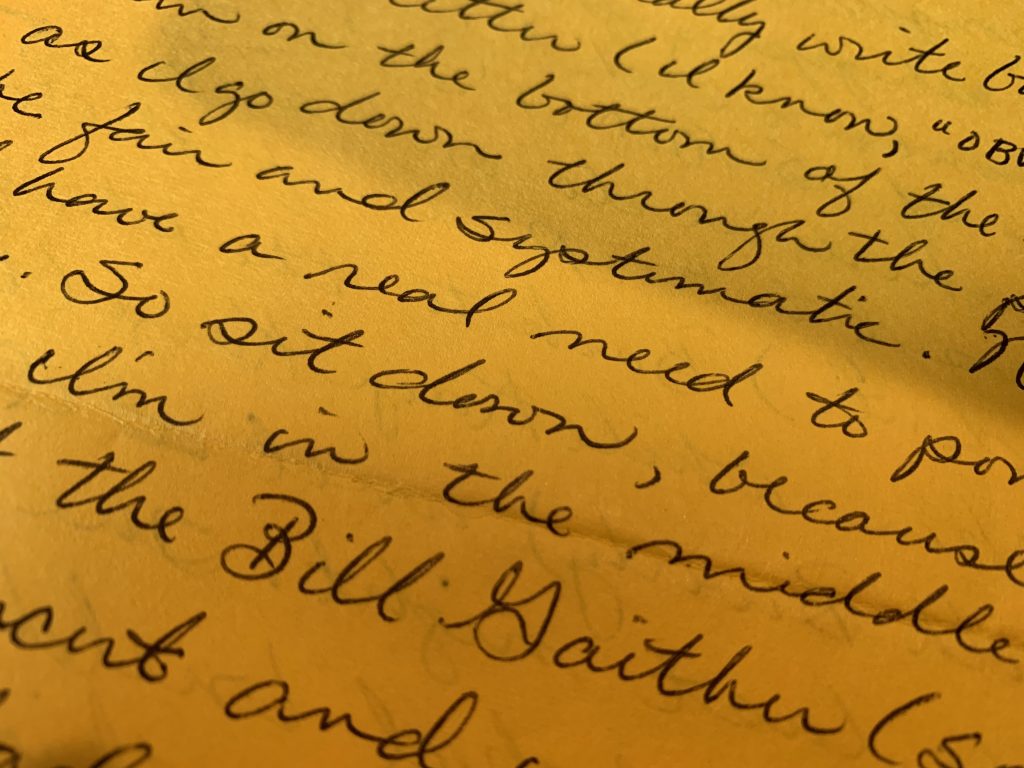

This week I got a glimpse into who I was in my very first ministry job. A friend, someone I’ve known most all of my life, a few years older and also seminary graduate, Cheryl, sent me a letter that I wrote to her in 1985.

It was the year I took off between high school and college. I took a gap year before that was cool. Or even a thing.

I drove myself so hard during high school. I graduated fourth in my class. Mainly because I sold annual ads during fourth period instead of coming back to algebra II when lunch was over. I was the annual editor along with my best friend Katie. And we used the lunch hour to go sell ads in the community. When I made that B in Algebra II, Mrs. Agron told me it was because I didn’t always come back to class at the end of fourth period. After lunch. Apparently, I missed some important things, because I was multitasking and doing things that I loved doing.

Even though I like to say I’m a recovering perfectionist. Truth is, I was always screwing things up just a little so as not to be perfect. I won’t unpack the psychology of that right now. But I’ll just note that I was a person who often pushes myself hard… going back as far as high school, middle school, elementary school. Oh good grief. I pretty much came into the world just as I am.

+++++++

So by the time graduation came I had edited the yearbook, lettered in soccer (don’t be impressed it was the first school-sponsored soccer team for girls, which equals a very easy letter). I was voted “most studious” which I truly, truly hated. As you likely know in high school, being intelligent and being attractive are generally considered mutually exclusive. This did not make me happy. I wanted to be “most likely to succeed,” but that was what my best friend Katie got.

Let’s be clear. We both appeared extremely studious because we were extremely smart. Some things were hard and required study, but quite a lot came relatively easily. And we both were as likely to succeed as any other Southern white girls can succeed along an academic trajectory. Katie is now a nursing professor, clinical teacher and researcher. I am a seminary professor, ethnographer, minister and writer. So with long and winding paths you could say we have both been studious and successful. But none of these things are exactly the point of my story today.

The point of my story is that I was indeed a Southern white girl. And memory clouds and obfuscates the ways that white supremacy shaped and disciplined me. My parents taught me explicitly that it was wrong to be racist. I knew it. And if you asked me yesterday, I could’ve told you some racist things that I witnessed and that I participated in, yet only truly recognized them as racist as an adult.

But then I got a letter.

And in that letter, I saw myself in a whole new light.

+++++++

I am teaching my students this semester and every semester for a decade that it is our job, as people who are racialized as “white,” to deconstruct our whiteness and our privileges. I’ve been saying things openly in this way and trying to practice what I teach and preach for many years. Yet my intent also falls short. And I fail to make my point or have the impact I hope in many cases.

I finished my dissertation in 2008 seeing more clearly than ever just how Southern Baptists, the religion of my childhood and youth, were deeply complicit in evils of racism. And seeing how that reality cost many, many lives through the eras of the antebellum South, the Civil War, Reconstruction, the Jim and Jane Crowe era, And yes, including the civil rights movement. Southern Baptist failed miserably in every era. But I thought I was different. I thought I had been raised differently, and the explicit messages that I was raised on were different.

But that didn’t actually make me different.

Belief and practice are not the same thing. And while I believed racism was wrong for many years, I now have evidence of my racist practice in my own handwriting. Racism and white supremacy shaped my identity in thoughtless and cruel ways. It made me into a person that now 30+ years later I truly despise. Standing alongside Dr. Chanequa Walker-Barnes and the Psalmists of ancient Israel, I can pray in my own prayer of confession and honesty that I do hate white people already, starting with myself.

Dr. Walker Barnes confesses that she has let white people off the hook too often for their racism. Me too. Again starting with myself.

+++++++

One of the things I hear often especially from white pastors that I’ve met along the way in my life and ministry and seminary education and research, Is the “we have to outlast them“ theory.

It goes something like this. A progressive white pastor goes to a new church. He or she is only there a short time and starts to see how the white congregation has some openly racist members. They hear the jokes, the snide remarks, the thinly veiled biases that show up in the form of little changes in tone of voice, or little ticks of the body. These gestures signal that non-white people aren’t OK (read: less than fully human). These “good folks” would never say the racist words openly, although of course some of them would. And do.

When the pastor witnesses this behavior, and is not sure exactly what to do… Call it out? Confront the person? Challenge the implication? Argue? Report it to the deacons. Oh wait, that was a deacon. The pastor learned about implicit bias in Seminary. But they probably didn’t practice on what to do in the moment when it happens.

So then, Deacon Smith says, “But what would we do? What if it lowers the value of our property? You know. If they move in…” And this is said with a shoulder shrug, hand lifted and a slight tilt of the head. This in response to a conversation about a small-town neighborhood shifting from all white homeowners to a greater diversity of Black and Latinx neighbors. The new pastor thinks he or she must simply outlast or outlive the lives of folks who speak in this way.

Fortunately my first full-time ministry call put me in the orbit of a pastor and mentor who would challenge these kind of comments and gestures. Sometimes with humor, sometimes with anger, sometimes with a question. And he would preach addressing the problems of racism in our town head on, and he would rally the congregation to join the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day march. And he would model for all of us ways to confront the indignities and the dangers of racism.

But it wasn’t enough.

It worked to get some of what I saw written in that letter from my 19-year-old, barely-graduated-from-high-school self, out of me. Some of what my pastor and my community of faith taught me gave me better language and more courage to not be defined by my whiteness alone.

That first call taught me little about white privilege, however. I learned very little about how my efforts to resist racisism often merely re-centered my whiteness and my power. It’s subtle stuff this trying to change, especially when you’re swimming as a white person in an ocean of whiteness. I was serving a church just a few miles from Crabapple First Baptist Church. That church was home to Robert Aaron Long. The 21-year-old, North Georgia man believed he needed to extinguish his sexual desire by killing people who worked in massage parlors. Six people who died were women of Asian descent. Southern Baptist purity culture and racism are deeply entangled.

+++++++

Please don’t walk away right now thinking I’m only telling a story about the South. Or even Southern Baptists. I am not.

The problems of racism and the structures of white supremacy and the power of white privilege extend in every direction cross every border of the United States and beyond.

Now looking back from my 50s into that spring when I was 19, I am reading my own words in my own handwriting. And I see how racism was in every joke that I tried to make. It’s so embarrassing. But it’s so important to name and deconstruct. Because it’s part of who I am. And repentance matters. But we’re not there yet, so let’s not get ahead of the story.

On Friday, I’ll tell you the rest. For now, please save this date!